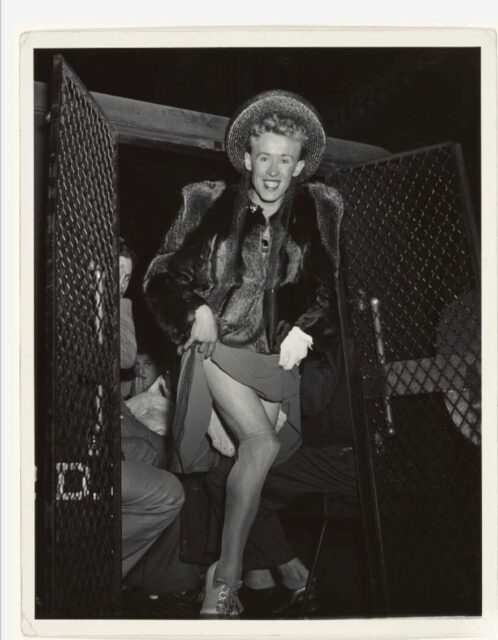

Photography has always been more than a way to freeze a moment in time. Since the 19th century, the camera has captured intimacy, defiance, and the many ways queer people have expressed identity. Through the Queer Lens: A History of Photography revisits this visual record, unearthing how photographs became evidence of both survival and celebration for LGBTQ+ communities.

A Medium of Visibility

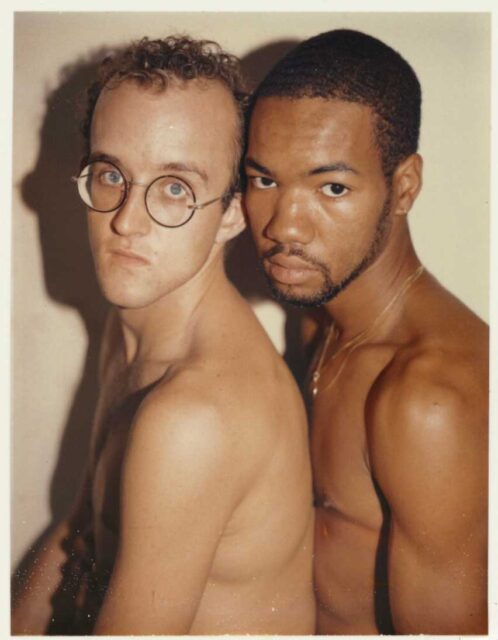

From its earliest days, photography offered something other art forms could not: immediacy. A portrait could document forbidden relationships or signal queer identity with subtle gestures. These images were often exchanged in private, providing a form of affirmation in a world that did not allow open recognition.

Even during periods of censorship and erasure, photographs remained a lifeline. Many were hidden, destroyed, or suppressed, yet enough survived to testify to the resilience of queer expression.

Reclaiming “Queer”

The exhibition also addresses the complicated history of the word “queer.” For decades, it was used as a slur. Today, many have reclaimed it as a term of empowerment and inclusivity. Wall texts within the show explain this shift, framing “queer” not as an insult but as a broad, gender-neutral umbrella that acknowledges people often overlooked by narrower identifiers.

The curators emphasize that the term is used intentionally and respectfully, honoring the diversity of identities represented in the collection.

A Shared Archive

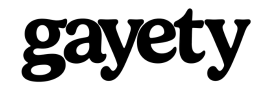

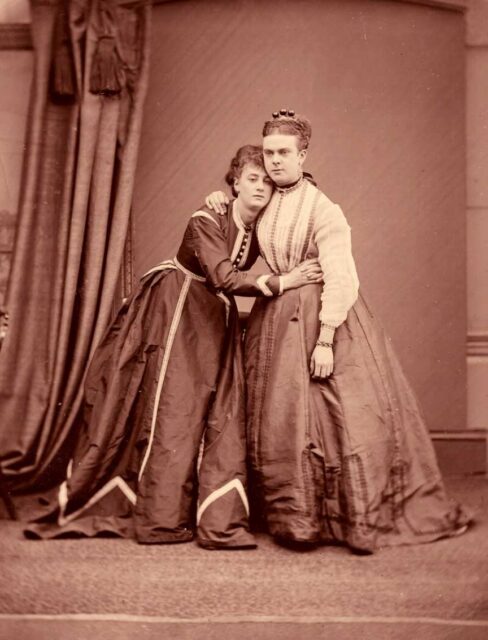

Through the Queer Lens highlights photography’s role in building community and shaping culture. The exhibition spans private snapshots, staged portraits, and images that later became touchstones of queer visibility. Each photograph carries evidence of how individuals navigated identity, connection, and survival through a changing social landscape.

By bringing these works together, the show creates a visual archive that resists disappearance. It reminds visitors that while queer lives were often pushed to the margins, photography preserved fragments of truth that could not be erased entirely.

Explore the Book

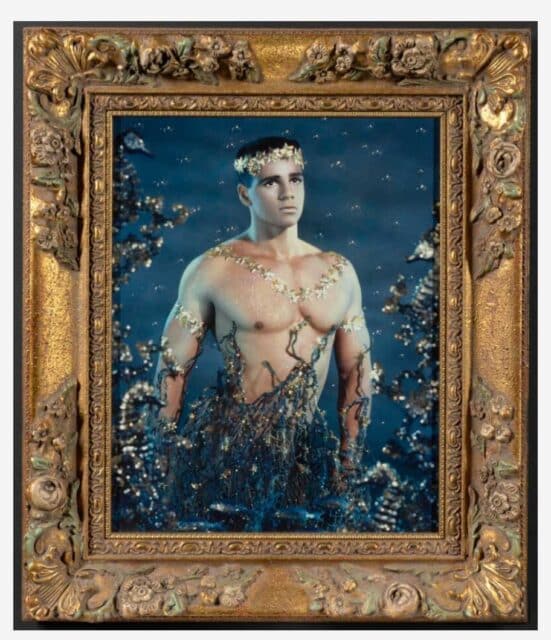

Photography’s power to capture reality, or a close approximation, has always been intertwined with identity. Since the camera’s invention in 1839, queer communities have used the medium to affirm themselves, resist erasure, and celebrate connection.

The Queer Lens book, published to accompany the exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum (June 17–September 28, 2025), expands on these themes. It features essays by scholars and artists exploring queer culture and identity, alongside a rich selection of images: portraits, visual records of kinship, and documentary photographs of early queer groups and protests.

![Angela Scheirl [now A. Hans Scheirl]. 1993, Photo: Catherine Opie. Silver-dye bleach print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Helen Kornblum in honor of Roxana Marcoci. © Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Naples](https://gayety.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/queer-lens-1-1-509x640.jpg)

The volume offers readers a deeper look into how photography has shaped queer visibility, making it an essential companion to the exhibition. Interested readers can purchase the book here.

Accessibility and Language

In keeping with its mission of inclusion, the exhibition is presented in both English and Spanish. This dual-language approach underscores the curators’ intent to make queer history accessible to wider audiences and to affirm that these stories belong to everyone.